Rodin the Modernist?

Rodin is generally considered to be the founder of modern sculpture; he certainly is one of its best, but does Rodin’s sculpture qualify as modernist sculpture? He came to prominence at the turn of the 20th century, as Victorian Britain died, and the Kings and Queens of France were fading out of living memory. His death on November 17th, 1917, a year before the end to the great war, dissipated his chances of partaking in the literary modernism that was about to bloom in the continent around him. As modernism grew in both art and literature Rodin was looming large, a death mask watching the procession.

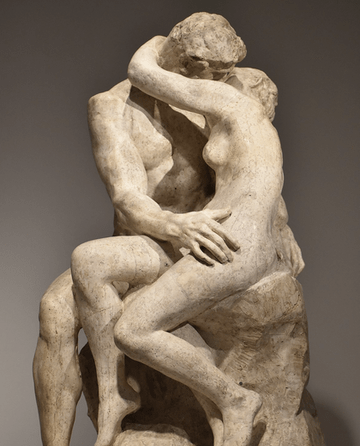

The negation of stereotypical story types, narrative structures, and use of grammar in modernist literature is to me the counterpart to Rodin’s most worthy structures. The stream of consciousness that Virginia Woolf uses in Mrs Dalloway (1925) is akin to the stream of consciousness that pours forth in the movements and the relations between bodies in Rodin’s work. This can be seen in the Gates of Hell (1880-1917), as you follow around all the retellings and interpretations of Dante’s Inferno you follow the stream of consciousness of the sculptor. Leopold Bloom from James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) is the walking man, pondering powerfully through the streets of Dublin. In Ezra Pound’s short poem In a Station of the Metro (1913) he compares the faces in the subway with petals on a bough. The images he seeks to convey relate to urban life, which at this time in Paris is being radically modernised and accelerated, to nature. Imagism was Pound’s phrase; it was the art of conveying clear cut images in precise language. Isn’t this exactly what we find Rodin doing in his sculpture? The sculptor who has no words but a title, which in Rodin’s case was often changed (The Age of Bronze for example). The marriage of modern urban life and nature was quintessential to Rodin. He often combined the two by finding the natural in the modern.

Renaissance Masters in Modern Paris

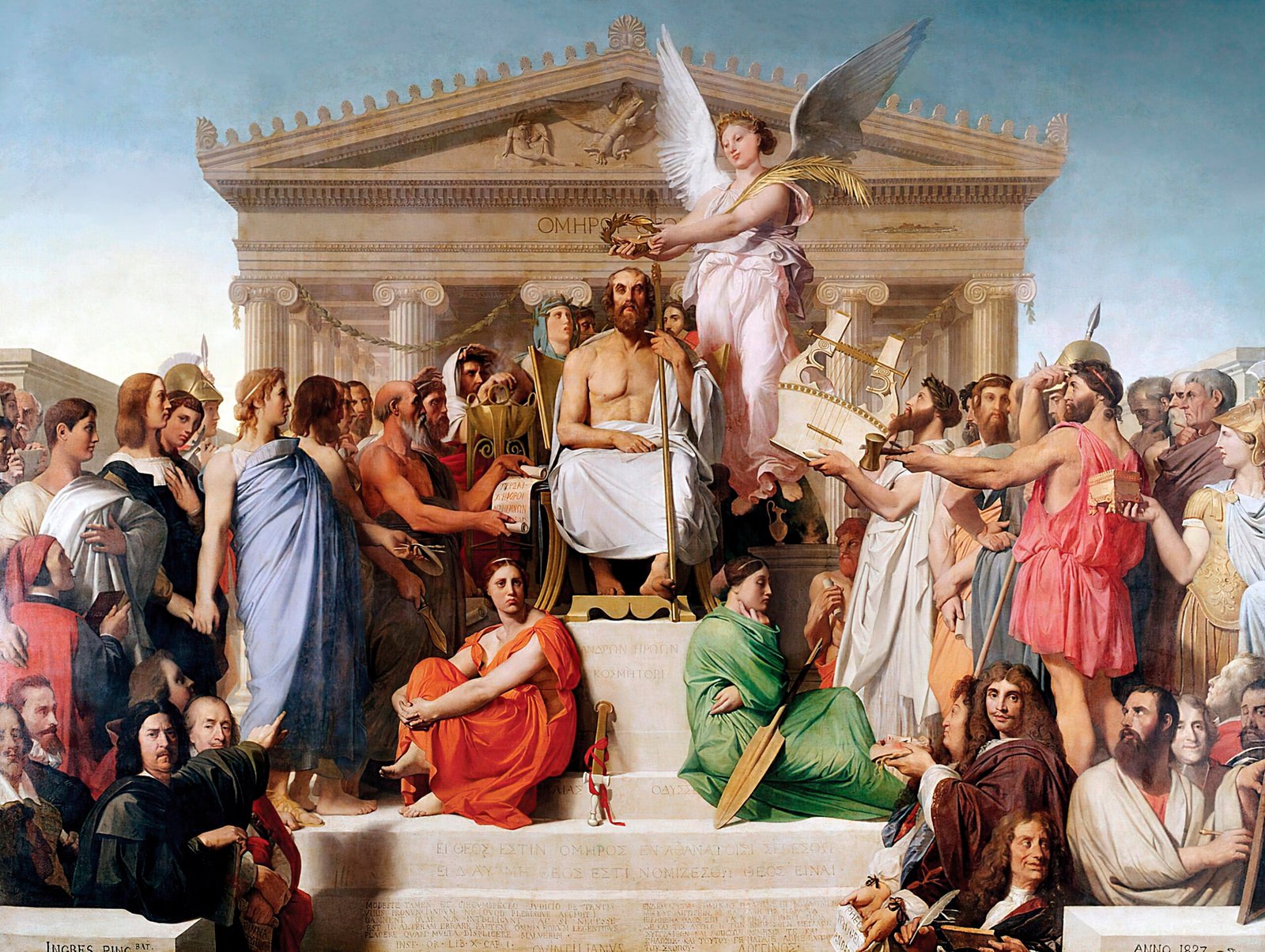

Rodin disregarded the classical motifs and strict rules which were deployed by the École desBeaux Arts in Paris and looked to nature for inspiration and guidance. He was rejected from the École des Beaux Arts and this rejection is what prompted Rodin to develop his own style. He was often criticised, by people of the same cloth that rejected him from the École, for depicting allegorical figures against the grain. Towards the end of the 19th century, he was further criticised for the eroticism found in his sculptures and drawings, but at this juncture he was already considerably famous, and he was able to weather the storm that placing a crotch directly under Victor Hugo’s nose seemed to rouse. Without a master and erupting with his own unique ideas Rodin rejected preeminent forms of classical sculpture which were in vogue during the second empire. Consequentially, he journeyed to Rome on a pilgrimage to learn the “secrets” of Michelangelo where he studied the great master in hope to “discover the principles upon which the compositions of Michelangelo’s figures were found”. In a letter to his pupil Bourdelle Rodin sates that it was “Michelangelo [that] liberated [him] from academicism”. Ruth Butler in her biography The Shape of Genius surmises what Rodin had learned from his new master; it was to breathe life into the human body and throw away the formulaic quality of contemporary sculpture. Rodin’s figures became more realistic, they moved and breathed. Rodin was able to imbue his sculptures with emotions, the nature of the human body was championed in its natural guise.

Rodin and the People

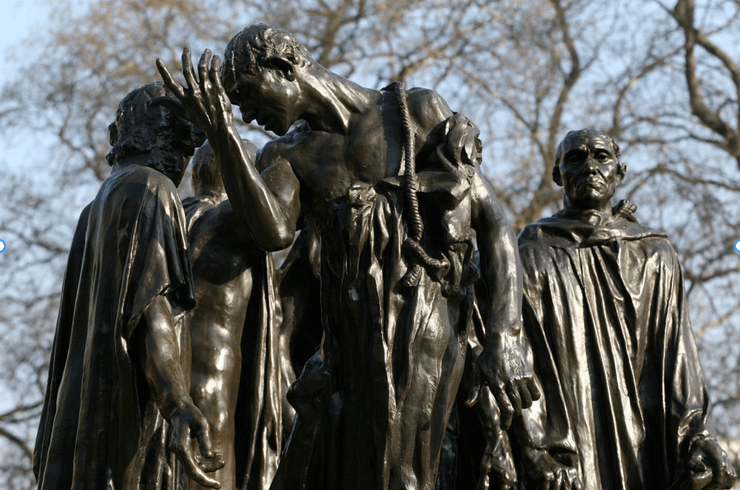

Moreover, he looked to develop the relations between the subjects he chose. The Burghers of Calais (1889) is a famous example of this; a traditional monument of this size would rise to the sky in a triangular shape and stand tall on a plinth. The monument would show heroism and bravery. Rodin opted out of these tropes. He placed the six figures on a wide and low plinth close to the ground and concentrated his efforts on having the subjects interact with the viewer. The depiction by Rodin shows no apparent heroism of bravery. The grandeur is in the story that the monument represents and this true to the tale retelling shows the anguish, desolation, and fear that each of the brave men went through on that day. Rodin’s break from the contemporary strangle hold of French sculpture is an apt comparison to the modernist writers who sought to break from traditional narrative forms. Samuel Beckett striped his writings of all unnecessary material in the same way that Rodin would disengage with defunct compositions to leave a natural foreverness.

Throughout most of Rodin’s youth and up until he was successful enough, he was employed in ornamental sculpture workshops (most notably Carrier-Belleuse in Paris and Brussels). This removed him from Parisian artistic circles as he would work all day for someone else, and all night on his own projects. As Rodin’s works began to engage with a larger audience and were showed in the Salons on the 1880’s he was able to befriend other artists. Most notably he fell in with the Impressionist painters. Rodin’s sculpture was by no means Impressionist but the like-minded individuals who worked directly from nature and experimented with light became his companions. When Rodin had finished a sculpture, he would haul it outside and observe how the light interacted and played with it. During the Universal Exposition of 1889 Rodin showed with Monet at Georges Petit’s gallery. The show was a success for Rodin who became inundated with commissions. Rodin broke from tradition once again, it was not normal for a sculpture to show in a gallery, sculpture was a decorative game, building monuments on state commission and submitting to the salon. The exhibition succeeded in elevating Rodin in the public sphere. Rodin was also an admirer of the Impressionists and owned numerous works by Pissarro. During this time, he also befriended Renoir, Sisley, and Whistler.

Model, Muse, Femme Fatale

Towards the end of Rodin’s life, he was surrounded less by artists and more by women of all motives. Rainer Maria Rilke was his secretary for a short while in Meudon but was dismissed for being pally with his associates. After Rilke, a string of women took care of his correspondence and all were enthralled with the genius and sought to gain something from him. Naturally, each outed each other, and a sham marriage arranged by Judith Cladel (a well-meaning follower of Rodin whose soul wish was to be in charge of the Musee Rodin) and a string of bureaucrats to unite Rodin with his life partner Rose Beuret, to flounder any secret will and to make sure all his works be given to the French government, as pre-agreed.

In the twilight of Rodin’s life, he travelled extensively and resembled more of a businessman, creating busts of English and American aristocrats for high prices. He put most of his life in the hands of the women that surrounded him. Jeanne and Henrietta Brady and Claire Coudert de Choiseul were infamous for their holds over Rodin and only intervention from Cadel and friends in the government prised Rodin out of their expensively manicured hands. However, it was women that were so influential to Rodin. He thought women divine and helped many female artists achieve their potential by being a mentor and confidant. He secured commissions for Camila Claudel and often bought some of her sculptures through a third party as well as paying rent for her studio.

Afterthought

Rodin’s greatest contributions to the foundations of the modern sculpture came between 1880 and 1900. The ideas that sprung forth during this time were to be the work that continued up until his death. It seems that the rest of the world was slowly catching up with him. It wasn’t until 11 years before his death that Rodin had a statue in his home and birthplace Paris, The Thinker (1902) was unveiled in front of the Pantheon on April 21st, 1906. The true measure of every genius is longevity and Rodin succeeded by inspiring and showing the way for all others who wanted to strike a truly modern flame within their respected fields.

Article by : William Rotherforth